Afghan Hospitality

This morning the car arrived very early to pick up me and Miho. I was confused because I had understood that we were going to be having dinner -- when we said 8 o'clock, I assumed we meant 8:00 pm. But no, Miho was correct, they asked that we arrive at 8:00 am. Bright and early we are welcomed warmly into the family house of our friends from yesterday. We climbed the stairs to our hosts' upstairs apartments. The home is decorated in traditional Afghan style, with minimalist empty walls and only elaborate Afghan carpets and kilms on the floor. We are immediately escorted into the hosting room and invited to sit down and enjoy some chai and chocolat -- tea and sweets. Miho and I accept with gratitude and begin the familiar process of sitting and drinking tea and being watched and not able to speak much in return. Rather, that is my routine. Miho has been here in Kabul for the past 3 years now, and her Dari is quite good. She is able to translate for me those things that gestures and facial expressions are not able to communicate. I understand that the girls want me to take them to the zoo and shopping. I explain that I would love to take them shopping but that I cannot use the company cars for such expeditions with so many guests, and further that I will need to arrange for the car in advance. They are leaving for Pakistan the following day and today is our final chance to pass time together. They are disappointed but understanding.

After some time, we are invited to meet the elders of the family -- grandmother and grandfather (modar and padar kalaam). Grandfather is an extremely gracious man, eager to engage with me and express his gratitude to the United States for intervening and defeating the Taleban.  He tells me how bad things were during Taleban rule, how terrible everything was, and how grateful he is that the U.S. ended it all. I understand him perfectly, even though he speaks in rapid Dari and does not gesture like I do. I understand him because of the depth of feeling with which he communicates his memories, his gratitude, his relief, his appreciation, his warm welcome and pleasure at having me in his home. I am overcome. Here even more than in other countries, I as a U.S. American citizen represent for the people here the government of the United States, and I am thereby entitled to the feelings of both gratitude and anger, awe and disdain, envy and rejection that our presence and reputation evokes. His warm and free affection for me fills me with a desire to reciprocate, to share my love for his country, and more than anything, to express my own apologetic gratitude for such kindness and hospitality knowing I have done nothing to deserve this.

He tells me how bad things were during Taleban rule, how terrible everything was, and how grateful he is that the U.S. ended it all. I understand him perfectly, even though he speaks in rapid Dari and does not gesture like I do. I understand him because of the depth of feeling with which he communicates his memories, his gratitude, his relief, his appreciation, his warm welcome and pleasure at having me in his home. I am overcome. Here even more than in other countries, I as a U.S. American citizen represent for the people here the government of the United States, and I am thereby entitled to the feelings of both gratitude and anger, awe and disdain, envy and rejection that our presence and reputation evokes. His warm and free affection for me fills me with a desire to reciprocate, to share my love for his country, and more than anything, to express my own apologetic gratitude for such kindness and hospitality knowing I have done nothing to deserve this.

Grandmother expresses her pleasure with much quieter dignity. She smiles and nods. She takes my hand and pats it. She gestures for a photo together. We take several, pausing after each one to look at the digital preview on the tiny camera screen. She does not know what to say to me, but she is happy that I am sitting beside her in her home on the other side of the world from my own.

Grandmother expresses her pleasure with much quieter dignity. She smiles and nods. She takes my hand and pats it. She gestures for a photo together. We take several, pausing after each one to look at the digital preview on the tiny camera screen. She does not know what to say to me, but she is happy that I am sitting beside her in her home on the other side of the world from my own.

After some time, Miho and I decide that we should mention that we are going to have to leave soon. "But we thought you were staying for dinner!" I think they meant lunch. They have been planning an elaborate meal with those things that I mentioned yesterday that I enjoy so much -- ausak and mantu. They are disappointed to hear that we will need to be leaving earlier than anticipated. Apparently they had wanted us to arrive early only to pass the day together, and were planning a full table for the afternoon meal. They rush to accomodate our needs and soon everyone is in the kitchen together, preparing the ausak.

First, we must prepare the "pasta" dough. I wish I knew what the ingredients were for everything, but unfortunately, specific grains and vegetables and herbs and spices are not the most common words in daily conversation and I have not picked up the Dari for them. This description is therefore embarrassingly limited.

First, we must prepare the "pasta" dough. I wish I knew what the ingredients were for everything, but unfortunately, specific grains and vegetables and herbs and spices are not the most common words in daily conversation and I have not picked up the Dari for them. This description is therefore embarrassingly limited.

We prepare the dough -- rolling it, kneading it, rolling it, flattening it in that special flattening machine until it is about 3mm thin and ready to be sliced into long, thin noodles. These they will use in a different dish later on. The sister who wore the burqa yesterday is also in charge of flattening. Her hennaed palms and fingers work the dough and the machine with familiar and habitual agility. For the ausak, we take the flattened dough and cut it into little circles with a cup. Then we take these little circles and fill them with greens -- dill, I think, and a type of onion, and other herbs that I have not yet identified. Once they are filled, we fold the little circles over and press the edges between our fingertips with a bit of water to close off these tasty little pockets. They will be cooked in oil and smothered in some yummy meaty red sauce and yogurt sauce. I am thrilled at this authentically Afghan female experience. Minus, of course, the poverty and the subtle relief of being inside one's

The sister who wore the burqa yesterday is also in charge of flattening. Her hennaed palms and fingers work the dough and the machine with familiar and habitual agility. For the ausak, we take the flattened dough and cut it into little circles with a cup. Then we take these little circles and fill them with greens -- dill, I think, and a type of onion, and other herbs that I have not yet identified. Once they are filled, we fold the little circles over and press the edges between our fingertips with a bit of water to close off these tasty little pockets. They will be cooked in oil and smothered in some yummy meaty red sauce and yogurt sauce. I am thrilled at this authentically Afghan female experience. Minus, of course, the poverty and the subtle relief of being inside one's  own house rather than outside in the oppressive public where women must be cautious about showing their bodies, faces, hair or talking too freely with people who are not related.

own house rather than outside in the oppressive public where women must be cautious about showing their bodies, faces, hair or talking too freely with people who are not related.

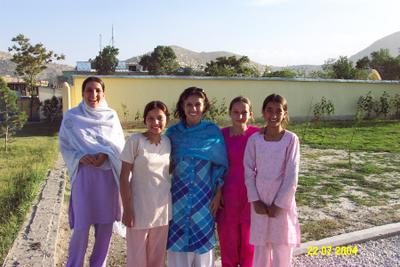

We finish preparing the meal and spend some time taking photos of each other. Everyone wants to have multiple pictures taken of themselves -- they are thrilled to see what they look like on camera. I encourage them to smile. I say, "with teeth!" and they laugh freely. The brother comes in and poses with a serious face that could easily pass for displeasure. Finally enough of them exhaust their desire to be photographed to convince the rest that it's enough. We adjourn once again to the sitting room where the children spread a tablecloth and begin to set the delicious meal. As is customary, the guests are served first, then the elder men, then the male children, the female children, and then the women. Actually, the women usually eat what is left over after everyone else has been served and eaten their fill. During the meal they are scarce, in the kitchen mostly but sometimes gliding in unobtrusively to refill tea, refill plates, and neaten the table. I am always extremely uncomfortable with this. As a western woman I am given a more masculine status, and I feel the distance keenly. I wonder how long it would take me to figure out how best to deal with that. Perhaps I will discover it in the future.

The meal was wonderful and then it was time for our car to return. We said our good-byes with many a besyar tashakur, bamane khuda, huda hofez, tashakur on our part and a chorus of "I love you my sister I miss you you my friend forever I love you" on theirs. I wrote my email on a card for them and explained that it was something they could use to reach me from a computer. I also gave them my phone number, but really I knew I would likely never see them or hear from them again. Somehow our separate lives in such dramatically different worlds led us to each other for a brief and meaningful encounter wherein we were able to connect to one another as women, as people, and I was both extremely happy and sad at once to realize it.

I was able to gather that they are Afghans living in Pakistan, as refugees not yet returned home after the fall of the Taleban. One of the girls, with a beauty far more mature than her age, has been living in Germany, and wants to be a model. Living far away from her native Afghanistan where women and children go hungry and malnourished for want of food, she already exhibits symptoms of a poor body image in the

I was able to gather that they are Afghans living in Pakistan, as refugees not yet returned home after the fall of the Taleban. One of the girls, with a beauty far more mature than her age, has been living in Germany, and wants to be a model. Living far away from her native Afghanistan where women and children go hungry and malnourished for want of food, she already exhibits symptoms of a poor body image in the